Evaluation and policy clinics give graduate students opportunities to build partnerships and connect research to practice

Annalee Good started her career in education by teaching middle school social studies and civics in rural Spring Green, Wisconsin, more than two decades ago. After three years, she moved west for a two-year stint in a similar position in Hamilton, Montana.

“I fully intended for classroom teaching to be my life, but I also wanted to get my master’s degree and was fortunate to end up here,” Good says of UW–Madison.

Much of her graduate work within the School of Education centered on examining why teachers are rarely involved with the creation of education policy. Good eventually earned both her master’s degree (2008) and Ph.D. (2011) from the Department of Educational Policy Studies.

“After I finished my doctorate, I kind of got sucked in and wanted to remain a part of the university,” says Good, now an assistant scientist with the School of Education’s Wisconsin Center for Education Research (WCER) and the co-director of the Wisconsin Evaluation Collaborative.

“After I finished my doctorate, I kind of got sucked in and wanted to remain a part of the university,” says Good, now an assistant scientist with the School of Education’s Wisconsin Center for Education Research (WCER) and the co-director of the Wisconsin Evaluation Collaborative.

Since 2015, she has led both the WCER Evaluation Clinic and the Wisconsin Education Policy, Outreach, and Practice (WEPOP) initiative. The Evaluation Clinic is designed to match graduate students with community partners around Dane County to support small-scale program evaluation needs. WEPOP similarly utilizes doctoral students to work with practicing teachers to build the skills and tools necessary to better make their voices heard in education policy discussions.

“The two clinics really developed out of my own passion for connecting research and practice — with the goal of engaging diverse voices and making our work matter,” says Good. “It started with my dissertation on why teachers’ voices are generally absent in policymaking. It’s rooted in my interest in the Wisconsin Idea and trying to find more effective ways to link the expertise and services of UW–Madison with community partners.”

Such efforts are also designed to meet the needs of students, typically from the School of Education, who are searching for opportunities to apply the knowledge they are gaining in their graduate programs toward real challenges that matter to the communities UW–Madison serves.

Currently, there are about 25 graduate students engaged with the two clinics, with students working closely with a range of organizations and also meeting as a group biweekly. During these sessions, team members and Good discuss various projects, talk over triumphs and pitfalls, and further develop evaluation and policy skills.

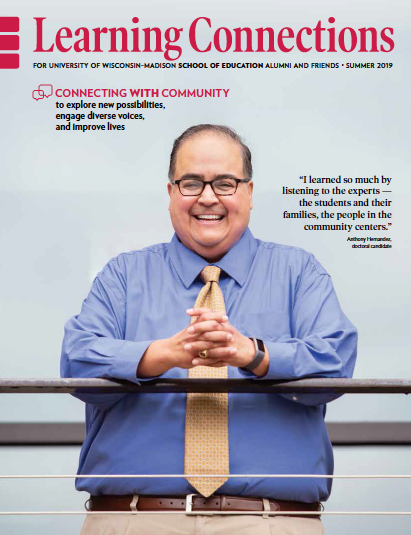

“As a student, you spend much of your time taking classes and reading and learning about theory and how things operate in the abstract,” says Anthony Hernandez, a doctoral candidate with the Department of Educational Policy Studies and a member of the WCER Evaluation Clinic. “The Evaluation Clinic is this very special place where you learn how the rubber hits the road.”

These opportunities are made possible via strong community relationships, with funding and graduate student support provided by WCER, the School of Education’s Network Fellows program — which connects graduate students to community partners to engage in impactful projects — and additional grant backing.

While opportunities to gain structured, organized, and applied experiences are commonplace in some areas of study — such as medical and law school settings — clinical preparation opportunities are not always prevalent at other institutions for those pursuing graduate work in the education realm.

“Learning how to work with and be of great value to community partners is a skillset,” says Good. “Projects evolve, restrictions are placed, and resources become limited. Your work isn’t theoretical anymore. Learning how to deal with various hurdles and still do amazing work helps prepare our students for after they graduate.”

• • •

To partner with the WCER Evaluation Clinic, Good explains that the client must be a not-for-profit or government entity located in Dane County, and the program that’s being evaluated must be education-related, and community- or school-initiated. Partners over the years have included Centro Hispano of Dane County, Wisconsin Public Television, the Urban League of Greater Madison, and the Goodman Community Center, to name only a few.

Gwendolyn Baxley got involved with the Evaluation Clinic about four years ago, not long after starting her Ph.D. work with the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis. Baxley, who defended her dissertation in June, previously worked on community schooling initiatives as a member of the School of Education’s Network Fellows program.

Gwendolyn Baxley got involved with the Evaluation Clinic about four years ago, not long after starting her Ph.D. work with the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis. Baxley, who defended her dissertation in June, previously worked on community schooling initiatives as a member of the School of Education’s Network Fellows program.

Baxley explains that community schools affirm the social, emotional, physical, and intellectual well-being of young people and families by providing additional resources to the school and transforming school practices and structures. Community schools, for example, integrate services and practices like restorative justice, critical and culturally responsive pedagogy, health care, food access, tutoring, mentoring, after school programming, and more into school sites and neighborhoods.

During the 2016–17 academic year, the Madison Metropolitan School District (MMSD) launched its first two community schools at Leopold and Mendota elementary. Two more schools — Hawthorne and Lake View elementary — were added as community schools for this past academic year.

MMSD contracted with the Wisconsin Evaluation Collaborative, also located within WCER, to assess its community schools. “Annalee was fantastic in spending time with us and understanding what our goals are and helping us refine our systems and talk more deeply about data tracking,” says Aronn Peterson, MMSD’s community schools manager.

This past year, during her final year at UW–Madison, Baxley led this evaluation, working closely with MMSD, Good, and other graduate students within the Evaluation Clinic.

Baxley says the clinic is performing a formative, ongoing evaluation of the new community schools program, helping MMSD learn what’s working well, what could be strengthened, and where improvements are needed. The graduate students are in regular contact with school staff and district leaders, while also getting close to community members to gather input from children and parents.

“I’m gaining great experience doing observations, keeping field notes, and conducting interviews that are part of the reports we compile for MMSD,” says Yasmin Rodriguez-Escutia, a fourth-year doctoral student with the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis, and a member of the WCER Evaluation Clinic.

Peterson says members of the Evaluation Clinic have helped the district see a need to create more robust data tracking systems to better monitor all that’s happening in the community schools. In addition, the many conversations the graduate student evaluators are having with various groups help the community schools “keep the conversation going” in efforts to find success.

“The data and information Annalee and the graduate students are collecting and providing is thorough, detailed, and incredibly important,” says Peterson. “It’s a major factor in helping us make adjustments to our program.”

Similarly, members of the Evaluation Clinic have learned from MMSD leadership about frameworks for implementing community schools based on national standards for operating community schools.

Baxley says this work has helped her understand that it takes more than solid technical and statistical skills to succeed as a researcher and evaluator.

“This project reinforced to me the value of interpersonal skills and how you can only be successful if you learn how to build relationships with schools and families and different stakeholders,” says Baxley. “We, as evaluators, have some areas of expertise but it’s the people on the ground, the parents and the children and school staff, who are living these schooling experiences and really know what’s going on. As a researcher and evaluator, we need to find ways to bring those voices out.”

In particular, Baxley spent part of the past year working with MMSD to help uplift voices of parents of color involved in the community schools.

“We need partnerships from around the community to be able to support and elevate this work,” says Peterson. “The resources and knowledge base that UW brings to this project is a key factor in helping us find success.”

Hernandez, the doctoral candidate with the Department of Educational Policy Studies, enjoyed a similar experience over the past two years, when he completed an evaluation of the REAP Food Group’s efforts to deliver free meals over the summer to Madison children. During the summer months, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Summer Food Service Program (SFSP) helps provide students living in low-income settings access to free, healthy meals. In Wisconsin, the SFSP is administered by the Department of Public Instruction. And in Madison, MMSD is the main sponsor of SFSP, providing free meals and program oversight at nearly 50 sites across the city.

REAP, a local nonprofit that works to build sustainable, local food systems for the entire community, had received a two-year, $50,000 grant from the Wisconsin Partnership Program to implement a suite of expansion and outreach efforts to increase participation in Madison’s summer meals program. REAP then partnered with the Wisconsin Evaluation Collaborative to assess MMSD’s Summer Food Service Program and the recent improvement efforts via the grant that REAP was awarded.Hernandez led the evaluation efforts that identified ways in which the SFSP is underutilized. The team examined the challenges participants experienced that contributed to low SFSP participation rates, and looked into ways to improve the program’s effectiveness.

“We were practitioners on farm-to-school efforts, not trained evaluators. So we knew we needed help setting up the evaluation,” says Natasha Smith, who was with REAP at the time of the evaluation’s launch, and who today is director of child nutrition at Project Bread, an anti-hunger organization in Massachusetts. “We utilized the expertise of Anthony and his team to help us design and carry out this assessment.”

Hernandez and his team surveyed children and families at the different sites, conducted in-person interviews, and led several focus groups to gather stories about their experiences with the food program.

By doing more than simply collecting and tracking numbers of participants and meals served, the Evaluation Clinic members learned through their work, for example, that some of the lunches being provided weren’t culturally relevant or palatable to some populations. Not only was food in those instances going to waste, but parents would need to go home and make lunch for their kids.

Although the SFSP program is national, Hernandez says the project he led was one of the first evaluations of the initiative, with the Evaluation Clinic’s work providing valuable insights and data from which future endeavors can build off. Hernandez was able to present the report at the 2018 National Farm to Cafeteria Conference in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Says Hernandez: “I learned so much by listening to the experts — the students and their families, the people in the community centers. We have to table this idea that we work in the academy, so we know more than other people. If you do this work well, you can really leverage the resources of the university to benefit populations on the periphery of society. That’s part of our larger mission and is the Wisconsin Idea in action.”

Graduate students involved with the Wisconsin Education Policy, Outreach, and Practice (WEPOP) initiative receive similarly valuable experiences in putting their knowledge to use. Initially launched in 2014 as Wisconsin Policy, Outreach, and Practice, or WiPOP, this program builds off of Good’s longstanding interest in finding ways to help teachers engage in policy discussions.

Today, WEPOP is a university-based partnership with educators that builds Pre-K–12 teachers’ capacity around federal, state, and local policy initiatives, while providing spaces for teachers to collaboratively engage with policy issues. WEPOP further fosters ongoing, teacher-directed policy discussions with advocates, policymakers, and researchers.

“My experience at UW–Madison is that the Wisconsin Idea is really something that is lived and practiced and supported in a way that makes this type of work possible,” says Laura Chávez-Moreno, who helped launch the policy clinic before earning her Ph.D. from the School of Education’s Department of Curriculum and Instruction in the summer of 2018. Chávez-Moreno is currently a postdoctoral scholar at the University of California, Los Angeles’ (UCLA) Graduate School of Education and Information Studies.

• • •

The graduate students interviewed for this report said that the evaluation and policy clinics played important roles in their growth as scholars and researchers.

Baxley is beginning a one-year postdoctoral position this fall at Teacher’s College, Columbia University. She then will begin a position as an assistant professor at the State University of New York–Buffalo. There, she aspires to help the university build out its partnerships with community schools in Buffalo.“The Evaluation Clinic is a space to bridge the gap between research and practice,” says Baxley. “You learn so much through this process about what it means to do good work with a partner and what it means to use the methods you learn in the academy to understand and seek to address structures in schools. You get to see in real time how your work may help shift practices, structures, and processes within various space.”

Hernandez, meanwhile, explained how the experience also played an important role in bolstering his leadership skills.

“The project taught me how to take charge — all the while having this safety net of being able to lean back on Annalee and the group for their expert advice,” says Hernandez. “I learned how to manage partners and my workload on a large project, how to manage conversations, and how to listen to the experts in the field we are working with.”

Moving forward, Hernandez adds he’s excited for the chance to explore additional opportunities that can change lives.

“We are being developed as a cohort of researchers that will go and work across different domains,” says Hernandez. “But we’ll always be connected and I know we’re going to collaborate on projects in the future. I see this as being incredibly fruitful in the years to come.”

‘Teachers at the Table’ released

As a master’s student in educational policy studies at UW-Madison in 2005, the first class Annalee Good took was a course with Mary Metz on the sociology of teaching. And the first paper she wrote pondered why teachers aren’t more involved in the creation of education policy.

“Over the years, my graduate studies kept coming back to that structural question about why are teachers’ voices absent, for the most part, from these conversations?” says Good.

“Over the years, my graduate studies kept coming back to that structural question about why are teachers’ voices absent, for the most part, from these conversations?” says Good.

This past fall, Good authored a new book building off of her dissertation work and ongoing involvement with the Wisconsin Education Policy, Outreach, and Practice (WEPOP) initiative. The book is titled “Teachers at the Table: Voice, Agency, and Advocacy in Educational Policymaking.”

Policy reflects and shapes society’s beliefs about schools, teachers, children, learning, and society, as well as the power structures embedded in our communities and decision-making processes. If policy is a public response to perceived social problems, it matters who is at the table when the problems are defined, the agendas set, and the policy itself designed.

Good’s book is based on the premise that policy matters in education – and teachers matter to policy.